Into Shade and Shadow

Drawing light is a bit like drawing time. An intangible, ephemeral entity; quantifying light onto paper almost negates it, rendering it as a shadow – pun intended – of its former self. Like time, light exists to make sense of our surroundings. In order to do so it does not have to be sensible in itself. The following post on the position of light within art is inspired by my visit to the National Gallery to see the subliminal work of Joaquín Sorolla, a man who has had the well-deserved title of “Master of Light” conferred upon him.

Light has been inextricably woven in with art; through the centuries, various artists have sought to control it. Be it the dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio or Jackson Pollock’s deceptively mindless flicks of paint, light makes art, art. James Turrell puts it beautifully when he says, “Light is not so much something that reveals, as it is itself the revelation.” Most successful works of art use light not as a medium to convey a narrative but as a subject, as a living object to be rendered into reality, much as one would the expression on a person’s face or a specific moment in time.

It would be criminal to begin a post on drawing light without going back to 23 April, 1490, a day upon which Leonardo da Vinci began writing his book, simply titled “of Shadow and Light”. It is painstakingly scientific in its pursuit of defining light and shadow, with great emphasis laid on optics and geometry; but even in his guise as a scientist, da Vinci is poetic in his definition of light, calling the act of light hitting a surface percussion, thus endowing it with dynamism. He further describes light as one of the ‘spiritual powers’, in which ‘spiritual’ has the Aristotelian meaning of ‘immaterial’ or ‘imperceptible’, now understood to be energy without mass. Even the greatest mind perhaps of the past millennium then falls prey to defining light through the definition of shadow which seems almost unfair. In doing so, da Vinci raises a question that would go on to plague the best of artists… if all that can be rendered on paper is shadow, how can we draw light?

Although I am no da Vinci or Sorolla and certainly no Turrell, I do use the medium of canvas and paper to express myself. And when doing so, there are three salient features of drawing light that I keep at the back of my mind, explained below:

Object versus Surface

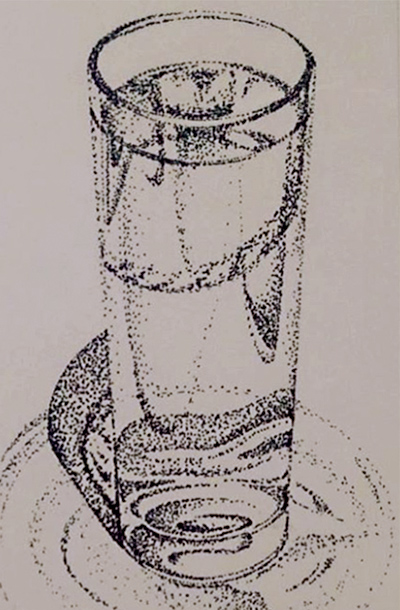

Light doesn’t exist in a single dimension, at least not in the world of art. Without a surface, there is no light. Without light, there is no object. Drawing a surface is easy, after all the eye sees in two dimensional planes stacked one behind the other due to our binocular vision. Drawing a surface is something we mastered as cave dwellers.

On the other hand, drawing in dimensions we can’t actually behold with merely our eyes is difficult, for we are attempting to render visually an object that should be read with more than one sense – that of vision and touch. This is where light comes in, bestowing the object with a mantle of authenticity that our eyes need in order to understand the three dimensions as real.

The Inequality of Shadows

A shadow is defined within the world of physics as the absence of light. In the world of art, the definition isn’t quite so simple. The success of a work of art is dependent upon how the artist renders the play of shadows cast. Not only is it important to distinguish between a cast shadow and a form shadow but also to differentiate a warm shadow from a cool one. The colour of a shadow is largely independent of the colour of the light that casts it, complicating matters further. A general rule of thumb that I like to follow is cool light, warm shadow; warm light, cool shadow, but… this is only true if both object and surface are a neutral white colour. Experimenting with your source of light, colour of object and colour of casting surface is key to making things real.

Daylight and Diffused Light

Multiple light sources or a distant light source like the Sun flatten the sense of volume in three dimensional objects due to the lack of drama that a point source can provide. They can be most challenging to work with but also produce the most realism in a work of art. Painting colours in flat areas to suit a diffused source of light relies upon value and hue rather than shadow and shade in order to establish visual hierarchies and make compositions seem “real”. A bit of artistic liberty (and by that I do mean exaggerating the Sun’s influence, or pretending that your diffuse source is in fact directional) when layering values and hues can also go a long way in rendering light correctly.

Here at Nulty we believe that drawing light can go a long way when it comes to understanding light and indeed spatial composition. It is for this reason that we lay emphasis on analogue sketching in combination with using digital methods of expression. We run workshops for the team (almost) every Friday as short breaks from the daily CAD and Dialux grind. And through these half hour zen sessions, explore and indeed express on paper, what it means to design with light.

Artwork: Seraphina Gogate