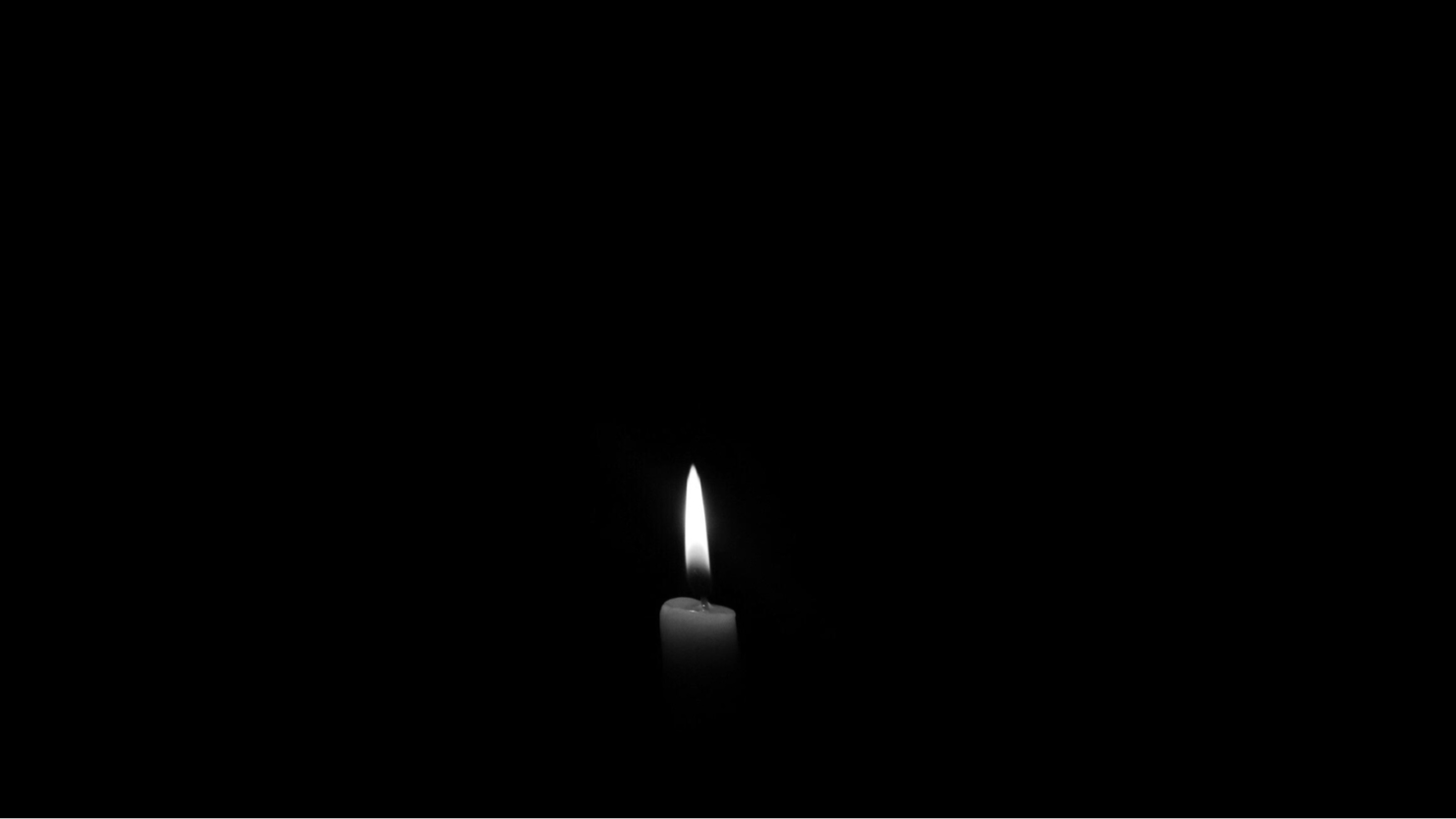

In Memory of Jun’ichirō Tanizaki the Japanese literary who explored the interplay of light and shadow, in contrast to the brightness of modern Western design.

Written by our Design Director Brice Schneider to commemorate 60 years since his passing (1886–1965).

~

Light reveals, but shadow gives meaning.

Somewhere along our pursuit of progress, we forgot that.

Our cities blaze through the night.

The stars have become theoretical.

Bedrooms pulse with standby LEDs.

Interiors are scrubbed clean of shadow, as if darkness itself were a design flaw.

We now measure light in mechanical terms, mistaking efficiency for advancement, counting lumens per watt, reducing illumination to data, and stripping it of its emotional weight.

But visibility does not guarantee connection. Brightness does not always bring clarity.

(Still from Ugetsu (1953), directed by Kenji Mizoguchi. Cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa. Sourced from Internet Archive, marked under the Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0.)

(Still from Ugetsu (1953), directed by Kenji Mizoguchi. Cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa. Sourced from Internet Archive, marked under the Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0.)

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki once asked us to pause, not in nostalgia, but in perception. In Praise of Shadows is often remembered as an ode to darkness, but it is, in truth, an ode to restraint. To glow. To half-tone. To the quiet shimmer at the edge of visibility. He attuned himself to the soft gradations between light and shadow, showing us how these thresholds shape mood, ritual, memory, and meaning.

But what if we extended his thinking further? What if In Praise of Shadows was not only a reflection on dimness, but the foundation for a new praise of night?

If Tanizaki once marvelled at a candle’s reflection on lacquered surfaces, what would he make of a world where even astronomers can no longer see the stars from most cities? Where children grow up never knowing the Milky Way? Where night itself, once a realm of silence, orientation, and wonder, has been so drenched in artificial light that we’ve lost not only the drama of nightfall, but the intimacy of shadow?

In a sense, we haven’t just lost night. We’ve lost the very conditions through which awe once arrived. And not all nights are the same.

The night of a desert plateau is not the night of a suburban street. The night of a forest edge is not the night of a city square. One holds stillness, the other tension. These nights contain different genius loci, spirits of place shaped by geology, memory, and expectation.

So why should we approach them in the same way, or light them with a similar hand?

To design with light is to begin with questions, not solutions.

What kind of night lives here?

Who is it for?

And at what time?

These are not abstract inquiries. They shape atmosphere, tempo, and the trust we build into a space. Is this a night that invites stillness or alertness? Is it shared or solitary? Does it carry a rhythm, tidal, civic, migratory, ritual?

Night is not a blank canvas. It is a condition, a memory field, a shared ecology. When we light it indiscriminately, we erase more than darkness, we erase its context.

To work with night is to work with complexity. But the engineering-driven approach to lighting often flattens that complexity into binary choices: light or no light, seen or unseen, safe or unsafe. The real task is subtler.

Good lighting does not assert dominance. It enables transitions between light and dark, inside and outside, clarity and invitation.

Yet the gap between these poles has grown too wide. The difference between a fully lit space and one with no light is now so extreme that it hinders transition. As we flood one and erase the other, we lose the ability to move between them. And when extremes disconnect, contrast turns brittle. We need less opposition and more exchange. We need light and darkness to interact, to fold into one another with care.

That interaction doesn’t happen by accident, it must be crafted. Sometimes delicately. Sometimes almost invisibly. This is the designer’s deeper task: to shape light not just for clarity, but for resonance.

We can begin with shadows, but we must go beyond them.

A dappled pattern across a path can evoke the imagined presence of trees. A ripple of light on a wall may suggest water nearby. A flicker might recall flame. A soft diffraction can summon the memory of silk, or paper, or breath. These are not visual tricks; they are perceptual bridges between the built and the natural.

In these in-between languages, dapple, ripple, ambient veil, we return emotional depth to a space.

To illuminate a tree with dappled light is not just to reveal its form, but to amplify its presence. The interplay of filtered light mimics moonlight, tricking our senses just enough to allow the imagination to complete the scene. A secondary dapple, cast onto the ground, extends the illusion, softly increasing coverage while maintaining a naturalistic feel. These gestures balance atmosphere and function, letting light support visibility without overpowering nuance.

To be effective, light must remain a quiet medium, not commanding attention, but supporting presence. When it echoes the world instead of replacing it, perception deepens. We begin to sense a place, not just see it.